Thailand doesn't want skint westerners not spending enough or paying tax. Therefore the authorities only allow holiday visitors one month on a tourist visa, by which time the "we're here for the temples and food" brigade should have spent all their holiday saving money. Keeping them for longer doesn't make much more financial sense.

Visitors on work permits are given stays of a year at a time, though we have to "show ourselves" every three months. It sounds it but it's not rude. All we do is pop in and out of the country, or nip in for a few boring hours at an office on the Rama IV boulevard so the uniformed folk at Immigration can plop another stamp onto our passport. Most non residents chose to pop out of the country to somewhere close. There's a fair few of us who fly in and out of Phnom Penh, short time, on "visa runs."

On my run to PP I like to home down at the homely Foreign Correspondents Club and stay for a few nights before catching the plane back home. On my latest trips I've taken time to photograph some "New Khmer Architecture" from the 1960s and early 1970s. There's nowt New after the early 1970s given that the Good Old Khmer Rouge emptied the streets, killed the architects and brought urban life to a halt.

I've been reading up on a Cambodian architect called Van Molyvann. He's dead interesting and stil alive in his mid eighties. However, I did come across one syrupy and gushing article, nauseatingly written in the present tense, by Claire Knox. Phnom Penh Post, Friday 25th 2013 that had me going bananas at my computer.

I appreciate Claire's research and work, what I'm unhappy about is her style. It's a personal thing of mine. She starts, "Vann Molyvann, Cambodia's most revered architect, sweeps a creased hand over rows and rows of glossy books lining his teak bookshelf."

When I read such flowery drivel I spark off. I've a mental picture of Claire trying to do a Karen Blixen or Jane Austen or feeble, fluffy, emotional tart, writing up her Lonely Planet journal in a Phnom Penh hostel coffee shop on a three dollars fifty a day budget, with a daypack containing a thousand quid Nikon a four hundred quid iPhone, but no deodorant.

I get irritated and a little cross. "Cambodia's most revered living architect." I'll take that on. Okay everyone, name five Cambodian architects. I'm not a cynic (all the time) but Claire's not persuaded me of her architectural criticism credentials in that opening salvo. So she's not going to grab my attention and trust to convince me that she is one to tell me Vann Molly is up there on the top of this week's revered hit parade.

While I am on the first sentence, could we define "revere."

In my dictionary, here on my desk, it states "to have great respect for (someone or something): to show devotion and honour to (someone or something)". Revere might not be (one hundred per cent not be) the over embellishing word I would chose. Perhaps that's as I've a background in market research, surveys, attitudes and images.

"(Intro) Good afternoon, I'm conducting a survey about Cambodian architects and I would like you to tell me which living architects from this list (Showcard One, tick each as mentioned) you a. revere b. respect c. worship d. devote yourself to e. honour f. think is a good architect."

(On completion of "Part One. Living Cambodian Architect Section" go to "Part Two. Dead Cambodian Architect Section" Showcard Six...)

I haven't finished with sentence one. Not yet I haven't. "Vann Molyvann sweeps a creased hand over..."

"Sweeps a..." That would be Vann Molyvann's hand would it? I'm presuming it most likely is. Or is it a mannequin's hand with an artistic coating of latex to get the creases on. Maybe Vann Molyvann is sweeping his recently amputated left hand over the books as he holds it in his right non amputated hand, a little like how I flick a feather duster over my bookshelves. Being completely daft I could suggest the hand, a hand, is a hand from no one to do with Van Molyvann, for example, a hand recently blown off a victim of some mine clearing activity up on the north west frontier. Please. "Vann Molyvann swept his creased hand." Or even better, "Vann Molyvann swept his hand."

That's why I've strained the syrup. I am saving others from shouting at their computer screens as I did. I've macho'd the style and toughed up the diction. I'm sure Claire will understand and not get hissy.

Molyvann. My Legacy Will Disappear.

Rewritten by Me from some drivel written before by Claire

27th April 2104

Vann Molyvann swept his hand over rows of books on his teak bookshelf; books on the Angkorian Kingdom, Swiss chalets, the Italian Renaissance, Le Corbusier, 1960s modern Japanese architecture, Cambodian artisans and ancient Greeks.

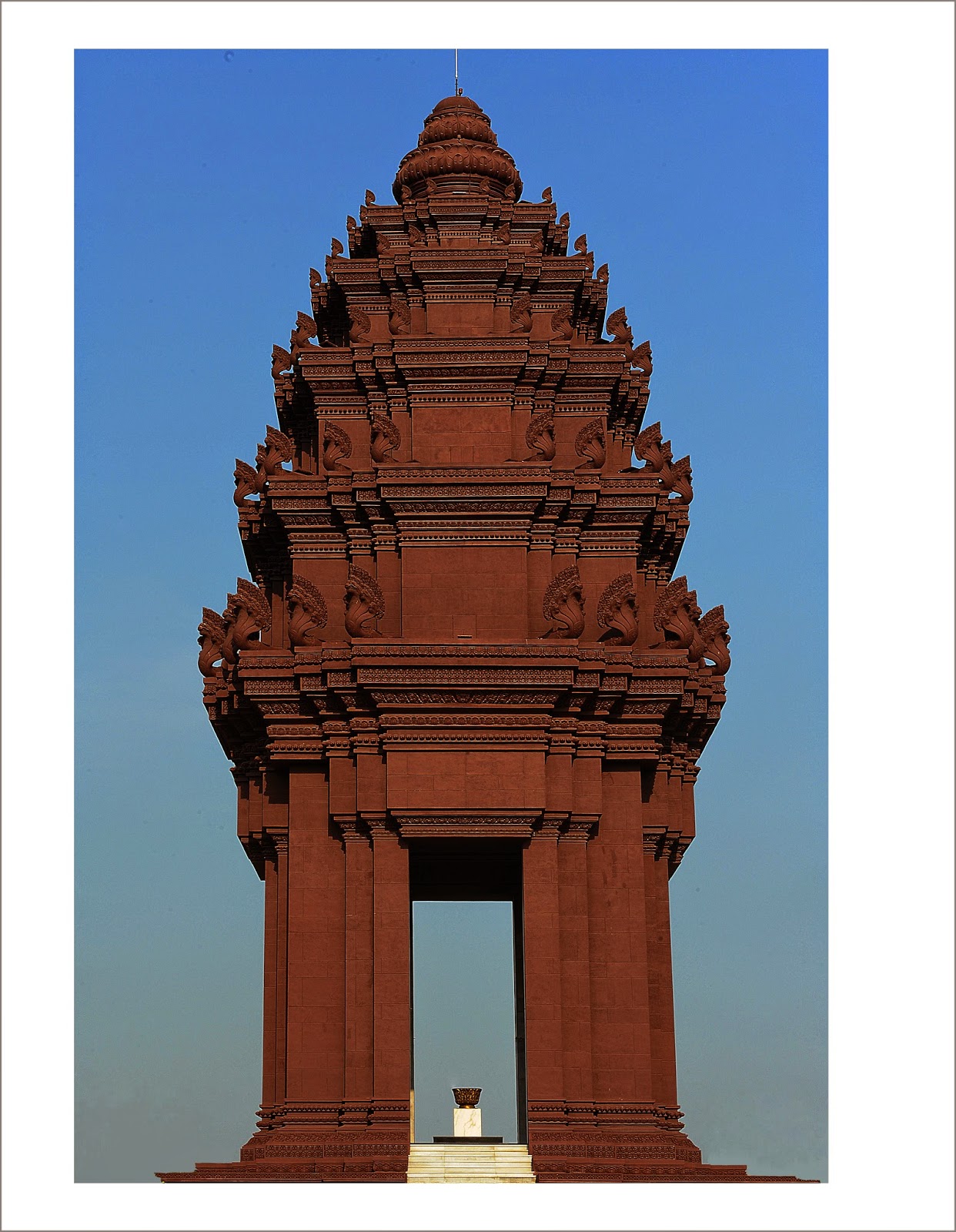

Molyvann's work during the 1950s and 1960s, the heyday of the King Norodom Sihanouk era, created some of the nations most iconic recent architecture; the National Sports Complex (now the Olympic Stadium), the Ministry of Finance, the White Building, the Institute for Foreign Languages, the Independence Monument and the fan shaped Chaktomuk Conference Hall, to name but a few. He believes the design of the Olympic Stadium is his magnum opus.

Vann Molyvann was born in Kampot, a coastal town in the Cambodian south, in 1926 and studied in Phnom Penh before he was a given a government grant to study law in Paris in 1946. However, he found his true calling learning architecture at L'Ecole des Beaux Arts. He absorbed the teachings of Swiss / French architect and urban planner Le Corbusier, as did other young Cambodian students; Lu Ban Hap, Chhim Sun Fong, Seng Sutheng and Mam Sophana.

The group became what is now known as the "New Khmer Movement" and were asked by Sihanouk to spearhead the design of new and remarkable civic structures after Cambodia took independence back from the French in 1953.

Molyvann, the most qualified of the group, was appointed Chief Architect of the Kingdom and Director for Urban Planning and Habitat. In thirteen years he was responsible for creating approximately one hundred buildings. I asked what it felt like to be accountable for the planning and design of a city aged thirty. He shook his head and with a smile said, "Of course it was an exciting, humbling experience for a young man - can you imagine?"

Molyvann's eyes sparkled when he recounted his experiences with Sihanouk.

"Sihanouk and I were colleagues. I had great respect for him. I can tell you a story about the way he gave orders, which was inspiring. One day in the sixties he called me, a French trained Khmer engineer, a physician and a few others. We had a meeting as the Royal Palace, and he said he had just come back from Indonesia. He said they have just built independence but they have plenty of universities, why don't we? This is the future. He said, you, Molyvann, you will create the Royal University of Phnom Penh. And I received a small Italian car, and went on a hunt for students and teachers, scholars, to create the council for the university.

Vann Molyvann built the linear housing blocks under the Bassac area project (which included the National Theatre Preah Suramarit) which contained the Grey and White Buildings (although Lu Ban Hap was credited with the latter) the only attempt made by a Cambodian government at a housing ownership scheme for civil servants.

"I was very proud of this. Each apartment was cross ventilated with cool, open space. But the ideology behind it was very close to my heart; allowing those who rented the houses to become owners after fifteen years. Cambodians are too poor for this to happen now. The ones there now (in the White Building, now slums) will never leave unless they are well paid, which is great. It is theirs. I am passionate for their rights, for housing and land rights."

Molyvann's doctoral thesis "Modern Khmer Cities" addressing the development and planning of Asian cities was completed in France when he was 82. He says he wrote it as a cathartic plea to the government to prompt better foresight into the planning of Phnom Penh; particularly the destruction of historic buildings.

As investment continues to flood Phnom Penh many colonial and New Khmer buildings have been ripped down and skyscrapers built in their place. The Grey Building is now the Phnom Penh Centre. The National Theatre has been razed.

Molyvann opened his book and scanned the section he has written on the country's property decrees and articles established since 1999. "These laws make me feel desperate for the Khmer people. I feel extremely sad... It is a systeme totalitaire. There is no hope left for my buildings. I believe most of them will go. I cannot elaborate any more. I am sick of it."

.